Responsible Mining

Mining is essential for modern life, providing the raw materials necessary for infrastructure, technology, and clean energy innovations.

To achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, the World Economic Forum estimates that 3 billion tons of metal will be required—equivalent to the weight of 300,000 Eiffel Towers. Mining plays a crucial role in fulfilling this need.

However, this necessity doesn’t grant the industry a license to operate without accountability. On the contrary, it imposes a responsibility to ensure that mining activities do not jeopardise the long-term health and wellbeing of people or the planet for short-term gains. Mining has the potential to significantly impact ecosystems, communities, and economies. Responsible mining mitigates these impacts, fostering trust among stakeholders and aligning operations with global objectives such as climate action, biodiversity conservation, and equitable development. Without these safeguards, the societal benefits of mining may be overshadowed by its costs, undermining its role as a driver of sustainable progress. Only through ethical and sustainable practices can mining contribute positively to society and the global transition to a low-carbon economy.

What is responsible mining?

Responsible mining refers to practices that prioritise environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and ethical governance throughout the entire mining lifecycle. This includes avoiding, minimising and mitigating environmental impacts, respecting human rights, ensuring worker safety, engaging with communities, and fostering long-term social and economic development.

What are some of the challenges when it comes to mining?

- Permitting and Regulations: Mining operations require extensive permitting and regulatory approval, often involving complex, time-consuming processes. These can include environmental and social impact assessments, public consultations, and compliance with national and international standards. While necessary for responsible mining, these processes can potentially delay projects.

- Long Lead Times: Developing a mine from exploration to production typically takes well over a decade. makes it difficult to meet rising demand for critical minerals.

- Supply Chain and Infrastructure: Mining often occurs in remote regions where infrastructure—such as roads, power, and water—must be built from the ground up. This adds cost, complexity, and potential environmental and social impacts.

Mining and the environment

The mining industry depends heavily on natural resources such as water and relies on maintaining supply chains. Irresponsible mining practices can lead to severe, far-reaching consequences that affect the environment, communities, and economies. These impacts undermine the potential benefits of mining and can cause lasting harm. ICMM members are committed to minimising mining’s impact on nature and promoting a harmonious relationship with the environment.

Mining operations span diverse landscapes, from mountains and polar regions to rainforests and urban areas. Each location requires tailored approaches to ensure operations respect the natural world. Our members are committed to operating in ways that:

- Acknowledge mining’s impacts on nature and take responsibility for minimising harm while transforming our relationship with the environment.

- Recognise Indigenous Peoples as vital partners, respecting their deep knowledge and connection to the land.

- Uphold high standards for responsible mining to address broader societal concerns.

- Foster cross-sector collaboration and implement robust monitoring to achieve a nature-positive future.

By way of illustration, high standards for responsible mining are especially crucial in regions where mining intersects with areas of global importance for biodiversity. Globally, studies show that 4.6% of active mining projects overlap with Intact Forest Landscapes, 7.5% with protected areas, and 3.2% with Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs). Mining’s environmental impacts vary depending on the resource being extracted, so tailored solutions are essential to mitigate harm and promote opportunities for nature.

Mining and society

The reputation of mining varies across regions, and it remains a controversial industry for many. This is due to a range of factors, including significant social impacts, both modern and historical. ICMM members strive to be the partner of choice for host countries and communities in developing mineral resources. Ensuring that investments enhance local and national social and economic development is a key goal.

Research by ICMM demonstrates that large-scale mining can provide low-income countries with vital economic boosts, helping to reduce poverty and reintegrate into the global economy. In areas where these benefits have not been realised, strengthening public sector governance is crucial. Companies can support these efforts through involvement in multi-stakeholder partnerships. However, such outcomes cannot be achieved by companies alone. The actions of governments, development agencies, organised labour, and civil society also significantly influence these outcomes. Governments bear fundamental responsibilities, and by fostering constructive partnerships, ICMM members can play a positive role.

-

Confronting historical injustices

Despite several recent examples of positive partnerships, resource extraction is one fraught with historical injustices, particularly when it comes to Indigenous Peoples. Over the centuries, Indigenous communities around the world have often been excluded from decisions about their own lands which has led, in many cases, to the exploitation of territories, and without adequate compensation or remediation. In many cases, Indigenous Peoples have borne the brunt of environmental degradation and social disruption caused by irresponsible mining practices.

These historical injustices cannot be overlooked, or underplayed, especially as we confront the global energy transition. Indigenous Peoples often have profound and distinct connections with their lands, territories, and other resources. These connections are tied to their physical, spiritual, cultural and economic wellbeing. Moreover, these lands are often home to some of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems, which Indigenous communities have long stewarded.

-

Acknowledging complex realities

In some cases, there may be differences in opinion on the value of mining versus potential societal impact. In these situations, it is essential that communities are given a meaningful say in the developments that affect their lands or territories. They must have the opportunity to meaningfully participate in decision-making processes, and those processes should prioritise the enabling of development aspirations, and protect environmental sustainability.

To navigate these complexities, human rights due diligence - the process of identifying who will be affected by mining activities, understanding how they will be impacted, and taking proactive steps to mitigate any harm - must be a core part of responsible mining practices. When done well, human rights due diligence enables good decision-making about if and how we develop natural resources for the benefit of all and without disadvantaging anyone, as far as possible.

-

Security and human rights

Mining companies have a real opportunity to lead by example—managing security in ways that also promote and protect human rights. The Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights (VPs) offer a clear, practical framework to help companies safeguard their people and assets while respecting the dignity and rights of local communities. By engaging actively in the VPs and effectively applying associated tools, companies can build trust, reduce risks, and demonstrate leadership in responsible business conduct.

Equally important is recognising the role of human rights defenders (HRDs) and civil society in shaping more inclusive and sustainable development. These individuals often offer early insight into potential risks and can be valuable partners in improving due diligence. When companies commit to protecting civic space and engaging constructively with HRDs, they not only support human rights—they also create the conditions for innovation, collaboration and shared value to flourish.

Momentum is building across the mining industry. With rising standards and stronger global collaboration, there is a genuine opportunity to embed respect for human rights into every level of decision-making. This is about more than avoiding harm—it’s about actively contributing to resilient communities, fairer economies and a safer, more sustainable future for all.

-

Managing resettlement

Mining companies do not have the freedom to choose project locations, as mineral and metal reserves exist in fixed locations. This can sometimes lead to community resettlement.

While government approval is needed, resettlement carries significant risks for both communities and companies.

Handled well, it can drive local development. Poorly managed, it leads to social and economic harm, project delays, and reputational damage. Minimising displacement should be a priority, and any resettlement must be carefully planned and resourced.ICMM’s Land Acquisition and Resettlement: Lessons Learned offers guidance on engagement, compensation, livelihood restoration, and impact monitoring. Applying these lessons helps reduce risks, uphold rights, and support sustainable development.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in mining

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) remain critical challenges for the mining and metals sector, impacting talent attraction, workforce potential, and stakeholder expectations.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) are not just ideals to aspire to—they are human rights, embedded in international standards and critical to the long-term success of the mining and metals sector. Yet despite growing awareness, the industry still faces deep-rooted challenges that continue to affect workplace culture, limit opportunity, and hold back progress.

Across the sector, troubling experiences of exclusion, harassment, and discrimination persist—particularly for women and underrepresented groups. Globally, women make up just 15% of the mining workforce, placing our industry among the least gender-diverse. And too often, those who do enter the workforce face higher risks of violence, bullying, and unequal treatment. These realities don’t just affect individuals—they shape how our sector is perceived, who feels welcome, and who sees a future here.

This isn’t just a social issue. It’s a business imperative. A diverse, inclusive workforce doesn’t just reflect society—it strengthens it. When people from all backgrounds are respected and empowered, companies see higher performance, stronger innovation, and more sustainable growth.

Progress is happening, but it’s uneven. Cultural norms vary across regions, and systemic barriers can look different depending on where and how a company operates. That’s why collective action matters. At ICMM, we are working to raise the industry’s shared ambition. We collaborate closely with our members and partners to identify common challenges, share lessons, and support practical, systemic change.

Our aim is to build workplaces where everyone can contribute fully, thrive without fear, and feel respected for who they are.

Change won't happen overnight—but with commitment, transparency and collaboration, we can create a mining industry that truly reflects the diverse, inclusive, and fair societies we want to help build. An industry that not only does no harm, but actively helps people and communities flourish.

Decarbonising mining

Metals and minerals like copper, lithium, and cobalt are essential for clean energy technologies, from electric vehicles to wind turbines. Our industry has both the opportunity and responsibility to be the backbone of a swift global shift to clean energy. Yet mining’s own carbon footprint poses a challenge—how do we supply these materials for decarbonisation without contributing to the problem? To be true partners in the energy transition, we must make their production as close to emissions-free as possible.

ICMM members—representing one-third of the global mining industry—have committed to net-zero emissions by 2050. This commitment is the guiding star of our decarbonisation efforts.

Efforts are already under way:

- Half of a mine's emissions are typically linked to the use of diesel-powered mining trucks. Innovations like ICMM’s ICSV initiative are advancing zero-emission vehicles, with widespread availability expected by 2030.

- Some of the world’s largest mining operations are already using 100% renewable energy, showcasing the industry’s potential to drive the growth of renewables.

- A large proportion of the emissions associated with mining comes from processing, transportation, and ultimately use (Scope 3 emissions) of materials. Leading mining companies recognise the need to decarbonise the entire value chain, from suppliers to customers.

-

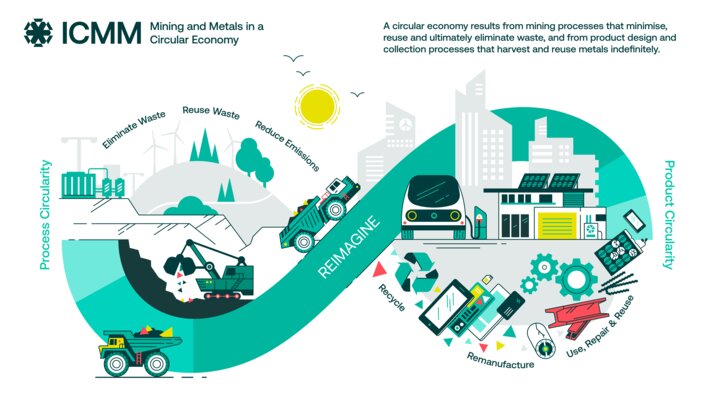

Promoting waste reduction, optimising water use, and regenerating closed sites are key to reducing mining’s environmental footprint. A circular approach to mining—one that prioritises both process circularity (e.g. waste valorisation, land remediation) and product circularity (e.g. reusing metals after their initial use)—can significantly cut emissions while maximising resource efficiency.

This dual approach ensures that metals are treated as durable materials—kept in use indefinitely rather than lost as waste—helping to reduce the need for energy-intensive primary production.

Expanding circularity across mine sites and their value chains not only minimises waste but also lowers carbon emissions at every stage of the life cycle, from sourcing and production to use and recovery. ICMM’s Tools for Circularity provide a common framework for understanding how mining and metals contribute to global circularity while supporting decarbonisation. They also help businesses identify opportunities, build a case for capturing circular value, and showcase real-world examples of success.

Mine closure

No mine is destined to last forever. Mineral and metal resources are finite, meaning the lifespan of any mine is limited.

Mine closure presents one of the industry's most significant challenges, requiring attention and financial provisions to manage safety, environmental, and social risks. While there are few examples of mines that have received closure certificates and been successfully transferred to governments or third parties, many more mines have simply been abandoned. This is unacceptable.

-

Integrated mine closure

Responsible closure involves careful planning and design from the outset, in consultation with relevant authorities and stakeholders, to achieve sustainable outcomes for mining companies, employees, the environment, and host communities.

Integrated mine closure is a dynamic, iterative process that considers environmental, social, and economic issues from the earliest stages of mine development, continuing throughout the mine’s life. Fundamental to this is the need to treat closure as an integral part of the mine’s core business. This means planning ahead for closure from the outset of operations.

ICMM's Integrated Mine Closure: Good Practice Guide promotes a disciplined approach to closure planning that seeks to address environmental, social, and economic issues from the outset and evolves throughout the mine’s life. The concepts apply equally to both large and small mining companies.

To support this approach, ICMM has developed tools such as the Closure Maturity Framework and Key Performance Indicators: Tool for Closure to build capacity and integrate closure into key operations.

-

Financial provisioning

Closure and legacy issues present material and reputational risks for ICMM members and the broader industry. Members are committed to making financial provisions to address the environmental and social aspects of closure. ICMM’s guidance, Financial Concepts for Mine Closure, enhances understanding of financial concepts related to closure and provides general guidance for various circumstances.